So as a member of His Majesty’s Royal Navy, one of the most famous ships that is still commissioned (but not the oldest still sailing) is HMS Victory. There is actually a draft there which I’ve never managed to get which involves duties like conducting Colours and Sunset as well as opening up for the public in the mornings. You also sleep on board when you do the night shifts as sailors are there in case there’s a fire. I do have a friend who served on her for a year in 2015. He confirmed to me that the Victory is in fact haunted and that he would be woken up during the night by footsteps on different decks etc.

So, like my article on Eleanor-of-aquitane, I thought I’d do a small article on this very historical ship. It’s the 11th December as I start this, a week before I break up for Christmas leave so I’m busy doing admin etc. I shall try to get this out in good time. I hope you all enjoy learning about her and if you ever get the chance please visit her.

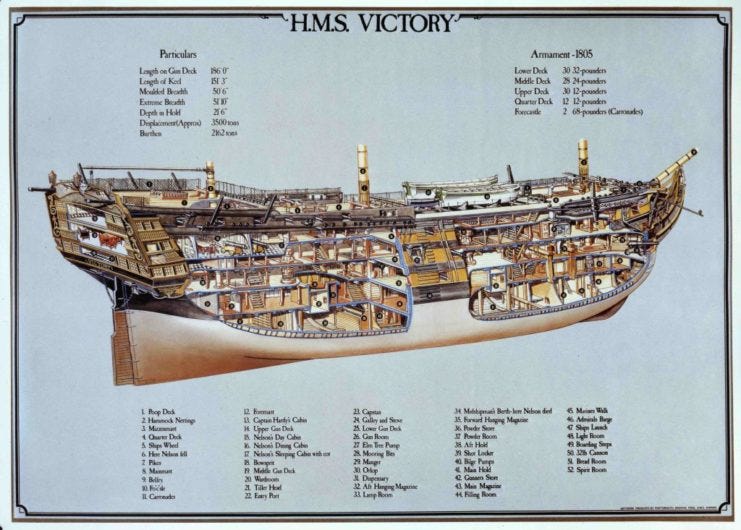

So…… HMS Victory. In December 1758. William Pitt the Elder, as Prime Minister of Great Britain, ordered 12 first rate ships to be built, one of which would become HMS Victory. What’s meant by a “first rate” ship. These were ships that were designed to be the largest ships of the line back in that time period. By the end of the eighteenth century, a first-rate carried no fewer than 100 guns and more than 850 crew, and had a measurement tonnage of some 2,000 tons.

10 ships were eventually built including HMS Victory. The naval architect chosen to design the ship was Sir Thomas Slade who, at the time, was the Surveyor of the Navy. She was designed to carry at least 100 guns. Her keel (the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a watercraft) was laid in the Old Single Dock at Chatham Dockyard on 23rd July 1759. A team of 150 workman were assigned to build her frame with around 6000 trees being used in her construction. The wood of the hull was held in place by six foot copper bolts, supported by treenails for the smaller fittings. Once the ship's frame had been built, it was normal to cover it up and leave it for several months to allow the wood to dry out or "season". The end of the Seven Years' War meant that Victory remained in this condition for nearly three years, which helped her subsequent longevity. Work restarted in autumn 1763 and she was floated on 7 May 1765.

Now at this point you might think that HMS Victory sailed the sea, destroyong enemy ships and hunting pirates in the Caribbean (yes I got it in) but you’d be wrong. Since there was no use for her she was moored in the River Medway. She was outfitted internally for the next 4 years before conducting her sea trials which were completed in 1769. She was first used against the French when you damn Americans decided you needed to be free from the amazing British Monarchy and the French decided to help them (I joke of course).

At this point I shall now gloss over HMS Victory’s battles until Nelson. I will post further links to these below. I hope that is okay with you readers. I shall continue.

Her first major battle was the First Battle of Ushant (1). The French tried to claim victory but I view this as more of a draw. During the battle HMS Victory opened fire on FS Bretagne of 110 guns, which was being followed by FS Ville de Paris of 90 guns. She and her fellow ships returned to Plymouth for repairs.

During her time in Plymouth, her hull, below the waterline was sheathed in sheets of copper to protect it from shipworm, a member of the mollusc family that love to bore into wood, eventually destroying the wood.

Her second major battle was the Second Battle of Ushant (2). Quite a significant battle but not for reasons you might think. This battle was fought in December 1781. It wasn’t a battle in the true sense. HMS Victory and 11 other ships of the line swept towards a French convoy of 110 transport ships, protected by 19 French ships and managed to capture 21 of the transport ships before escaping.

It is the aftermath that is the significant part. When news of the battle at Ushant reached Britain, the Opposition in Parliament questioned the decision to send such a small force against the convoy, and forced an official inquiry into the administration of the Royal Navy. This was the first of a succession of Opposition challenges that would ultimately bring about the fall of the government of Lord North on 20 March 1782 and pave the way for the Peace of Paris the following year, which ended the American Revolutionary War.

Her next major battle was the Battle of Cape St. Vincent in 1797. The battle occured on 14 February 1797 and was one of the opening battles of the Anglo-Spanish War (1796–1808), as part of the French Revolutionary Wars, where HMS Victory and her fellow fleet under Admiral Sir John Jervis defeated a greatly superior Spanish fleet under Admiral Don José de Córdoba y Ramos near Cape St. Vincent, Portugal. HMS Victory’s ship's log records how she halted the Spanish division, raking ships both ahead and astern, while Jervis' private memoirs recall how HMS Victory's broadside so terrified Princepe de Asturias that she "squared her yards, ran clear out of the battle and did not return". The British fleet not only achieved its main objective, that of preventing the Spanish from joining their French and Dutch allies in the channel, but also captured four ships.

After the battle HMS Victory returned to England where she was examined for her sea worthiness. It was discovered that she had significant weaknesses in her stern timbers. She was declared unfit for active service and left anchored off Chatham Dockyard. In December 1798 she was ordered to be converted to a hospital ship to hold wounded French and Spanish prisoners of war.

Now we find that whilst fate frowns on some people and things it smiles on others. In October 1799, HMS Impregnable (an ironic name I know) ran aground on her way home and could not be re-floated so was stripped of all weapons and dismantled. This left the RN short of a three-decked ship of the line. The Admiralty decided that recondition Victory. Work started in 1800, but as it proceeded, an increasing number of defects were found and the repairs developed into a very extensive reconstruction. The original estimate was £23,500, but the final cost was £70,933. Extra gun ports were added, taking her from 100 guns to 104, and her magazine lined with copper. The open galleries along her stern were removed; her figurehead was replaced along with her masts and the paint scheme changed from red to the black and yellow seen today. Her gun ports were originally yellow to match the hull, but later repainted black, giving a pattern later called the "Nelson chequer", which was adopted by most Royal Navy ships in the decade following the Battle of Trafalgar. The work was completed in April 1803, and the ship left for Portsmouth.

Now we come to, arguably, HMS Victory’s most important part of her history. Vice-Admiral Nelson hoisted his flag in Victory on 18 May 1803, with Samuel Sutton as his flag captain.

The Dispatches and Letters of Vice Admiral Lord Nelson (Volume 5, page 68) record that "Friday 20 May a.m. ... Nelson ... came on board. Saturday 21st. Un-moored ship and weighed. Made sail out of Spit-head ... when H.M. Ship Amphion joined, and proceeded to sea in company with us" – Victory's Log.

Victory was passing the island of Toro, near Majorca, on 4 April 1805, when HMS Phoebe brought the news that the French fleet under Pierre-Charles Villeneuve had escaped from Toulon. While Nelson made for Sicily to see if the French were heading for Egypt, Villeneuve was entering Cádiz to link up with the Spanish fleet.

The British fleet completed their stores in Lagos Bay, Portugal and, on 11 May, sailed westward with ten ships and three frigates in pursuit of the combined Franco-Spanish fleet of 17 ships. They arrived in the West Indies to find that the enemy was sailing back to Europe, where Napoleon Bonaparte was waiting for them with his invasion forces at Boulogne.

The Franco-Spanish fleet was involved in the indecisive Battle of Cape Finisterre in fog off Ferrol with Admiral Sir Robert Calder's squadron on 22 July, before taking refuge in Vigo and Ferrol. Calder on 14 August and Nelson on 15 August joined Admiral Cornwallis's Channel Fleet off Ushant. Nelson continued on to England on HMS Victory, leaving his Mediterranean fleet with Cornwallis who detached twenty of his thirty-three ships of the line and sent them, under Calder, to find the combined fleet at Ferrol. On 19 August came the worrying news that the enemy had sailed from there, followed by relief when they arrived in Cádiz two days later. On the evening of Saturday, 28 September, Lord Nelson joined Lord Collingwood's fleet off Cádiz, quietly, so that his presence would not be known.

Now we come to one of the most famous sea battles in Royal Navy History. The Battle of Trafalger.

On 21 October, Admiral Nelson had 27 ships of the line with 2,148 cannon, and a total of 17,000 crewmen and marines under his command. Nelson's flagship, HMS Victory, captained by Thomas Masterman Hardy, was one of three 100-gun first-rates in his fleet. He also had four 98-gun second-rates and 20 third-rates. One of the third rates was an 80-gun vessel, and 16 were 74-gun vessels. The remaining three were 64-gun ships, which were being phased out of the Royal Navy at the time of the battle. Nelson also had four frigates of 38 or 36 guns, a 12-gun schooner and a 10-gun cutter.

Against Nelson, Vice-Admiral Villeneuve, sailing on his flagship FS Bucentaure, fielded 33 ships of the line, including some of the largest in the world at the time. The Spanish contributed four first-rates to the fleet - three of these ships, one at 130 guns (SPS Santísima Trinidad) and two at 112 guns (SPS Príncipe de Asturias and SPS Santa Ana), were much larger than anything under Nelson's command. The fourth first-rate carried 100 guns. The fleet had six 80-gun third-rates, (four French and two Spanish), and one Spanish 64-gun third-rate. The remaining 22 third-rates were 74-gun vessels, of which 14 were French and eight Spanish. In total, the Spanish contributed 15 ships of the line and the French 18 along with some 30,000 men and marines manning 2,632 cannon. The fleet also included five 40-gun frigates and two 18-gun brigs, all French.

The Combined Fleet of French and Spanish warships anchored in Cádiz under the leadership of Admiral Villeneuve was in disarray. On 16 September 1805 Villeneuve received orders from Napoleon to sail the Combined Fleet from Cádiz to Naples. At first, Villeneuve was optimistic about returning to the Mediterranean, but soon had second thoughts. A war council was held aboard his flagship, FS Bucentaure, on 8 October. While some of the French captains wished to obey Napoleon's orders, the Spanish captains and other French officers, including Villeneuve, thought it best to remain in Cádiz. Villeneuve changed his mind yet again on 18 October 1805, ordering the Combined Fleet to sail immediately even though there were only very light winds.

The sudden change was prompted by a letter Villeneuve had received on 18 October, informing him that Vice-Admiral François Rosily had arrived in Madrid with orders to take command of the Combined Fleet. Stung by the prospect of being disgraced before the fleet, Villeneuve resolved to go to sea before his successor could reach Cádiz. The weather, however, suddenly turned calm following a week of gales. This slowed the progress of the fleet leaving the harbour, giving the British plenty of warning. Villeneuve had drawn up plans to form a force of four squadrons, each containing both French and Spanish ships. Following their earlier vote on 8 October to stay put, some captains were reluctant to leave Cádiz, and as a result they failed to follow Villeneuve's orders closely and the fleet straggled out of the harbour in no particular formation.

It took most of 20 October for Villeneuve to get his fleet organised; it eventually set sail in three columns for the Straits of Gibraltar to the southeast. That same evening, FS Achille spotted a force of 18 British ships of the line in pursuit. The fleet began to prepare for battle and during the night, they were ordered into a single line. The following day, Nelson's fleet of 27 ships of the line and four frigates was spotted in pursuit from the northwest with the wind behind it. Villeneuve again ordered his fleet into three columns, but soon changed his mind and restored a single line. The result was a sprawling, uneven formation.

At 5:40 a.m. on 21 October, the British were about 21 miles (34 km) to the northwest of Cape Trafalgar, with the Franco-Spanish fleet between the British and the Cape. About 6 a.m., Nelson gave the order to prepare for battle.

At 8 a.m., the British frigate HMS Euryalus, which had been keeping watch on the Combined Fleet overnight, observed the British fleet still "forming the lines" in which it would attack.

At 8 a.m., Villeneuve ordered the fleet to wear together (turn about) and return to Cádiz. This reversed the order of the allied line, placing the rear division under Rear-Admiral Pierre Dumanoir le Pelley in the vanguard. The wind became contrary at this point, often shifting direction. The very light wind rendered manoeuvring virtually impossible for all but the most expert seamen. The inexperienced crews had difficulty with the changing conditions, and it took nearly an hour and a half for Villeneuve's order to be completed. The French and Spanish fleet now formed an uneven, angular crescent, with the slower ships generally to leeward and closer to the shore.

By 11 a.m. Nelson's entire fleet was visible to Villeneuve, drawn up in two parallel columns. The two fleets would be within range of each other within an hour. Villeneuve was concerned at this point about forming up a line, as his ships were unevenly spaced in an irregular formation drawn out nearly five miles (8 km) long as Nelson's fleet approached.

As the British drew closer, they could see that the enemy was not sailing in a tight order, but in irregular groups. Nelson could not immediately make out the French flagship as the French and Spanish were not flying command pennants.

Nelson was outnumbered and outgunned, the enemy totalling nearly 30,000 men and 2,568 guns to his 17,000 men and 2,148 guns. The Franco-Spanish fleet also had six more ships of the line, and so could more readily combine their fire. There was no way for some of Nelson's ships to avoid being "doubled on" or even "trebled on".

As the two fleets drew closer, anxiety began to build among officers and sailors; one British sailor described the approach thus: "During this momentous preparation, the human mind had ample time for meditation, for it was evident that the fate of England rested on this battle".

The battle progressed largely according to Nelson's plan. At 11:45, Nelson sent the flag signal, "England expects that every man will do his duty".

His Lordship came to me on the poop, and after ordering certain signals to be made, about a quarter to noon, he said, "Mr. Pasco, I wish to say to the fleet, ENGLAND CONFIDES THAT EVERY MAN WILL DO HIS DUTY" and he added "You must be quick, for I have one more to make which is for close action." I replied, "If your Lordship will permit me to substitute 'expects' for 'confides' the signal will soon be completed, because the word 'expects' is in the vocabulary, and 'confides' must be spelt," His Lordship replied, in haste, and with seeming satisfaction, "That will do, Pasco, make it directly."

The term "England" was widely used at the time to refer to the United Kingdom; the British fleet included significant contingents from Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. Unlike the photographic depiction above, this signal would have been shown on the mizzen mast only and would have required 12 lifts.

As the battle opened, the French and Spanish were in a ragged curved line headed north. As planned, the British fleet was approaching the Franco-Spanish line in two columns. Leading the northern, windward column in HMS Victory was Nelson, while Collingwood in the 100-gun HMS Royal Sovereign led the second, leeward, column. The two British columns approached from the west at nearly a right angle to the allied line. Nelson led his column into a feint toward the van of the Franco-Spanish fleet and then abruptly turned toward the actual point of attack. Collingwood altered the course of his column slightly so that the two lines converged at this line of attack.

Just before his column engaged the allied forces, Collingwood said to his officers, "Now, gentlemen, let us do something today which the world may talk of hereafter.” Because the winds were very light during the battle, all the ships were moving extremely slowly, and the foremost British ships were under heavy fire from several of the allied ships for almost an hour before their own guns could bear.

At noon, Villeneuve sent the signal "engage the enemy", and FS Fougueux fired her first trial shot at HMS Royal Sovereign. HMS Royal Sovereign had all sails out and, having recently had her bottom cleaned, outran the rest of the British fleet. As she approached the allied line, she came under fire from FS Fougueux, FS Indomptable, SPS San Justo, and SPS San Leandro, before breaking the line just astern of Admiral Alava's flagship SPS Santa Ana, into which she fired a devastating double-shotted raking broadside. On board HMS Victory, Nelson pointed to HMS Royal Sovereign and said, "See how that noble fellow Collingwood carries his ship into action!" At approximately the same moment, Collingwood remarked to his captain, Edward Rotheram, "What would Nelson give to be here?”

The second ship in the British lee column, HMS Belleisle, was engaged by FS Aigle, FS Achille, FS Neptune and FS Fougueux; she was soon completely dismasted, unable to manoeuvre and largely unable to fight, as her sails blinded her batteries, but kept flying her flag for 45 minutes until the following British ships came to her rescue.

For 40 minutes, HMS Victory was under fire from FS Héros, SPS Santísima Trinidad, FS Redoutable, and FS Neptune; although many shots went astray, others killed and wounded a number of her crew and shot her wheel away, so that she had to be steered from her tiller belowdecks, all before she could respond. At 12:45, HMS Victory cut the enemy line between Villeneuve's flagship FS Bucentaure and FS Redoutable; she came close to FS Bucentaure with her guns loaded with double or treble shots each, and her 68-pounder carronades loaded with 500 musketballs, she unleashed a devastating treble-shotted raking broadside through FS Bucentaure's stern which killed and wounded some 200-400 men of the ship's 800 man complement and dismasted the ship. This volley of gunfire from the HMS Victory (A splendid piece of firing) immediately knocked the French Flagship out of action. Villeneuve thought that boarding would take place, and with the Eagle of his ship in hand, told his men, "I will throw it onto the enemy ship and we will take it back there!" However, Victory engaged the 74-gun FS Redoutable; FS Bucentaure was left to the next three ships of the British windward column: HMS Temeraire, HMS Conqueror, and HMS Neptune.

A general mêlée ensued. HMS Victory locked masts with the FS Redoutable, whose crew, including a strong infantry corps (with three captains and four lieutenants), gathered for an attempt to board and seize Victory. A musket bullet fired from the mizzentop of FS Redoutable struck Lord Nelson in the left shoulder, passed through his spine at the sixth and seventh thoracic vertebrae, and lodged two inches below his right scapula in the muscles of his back. Nelson exclaimed, "They finally succeeded, I am dead." He was carried below decks.

HMS Victory's gunners were called on deck to fight boarders, and she ceased firing. The gunners were forced back below decks by French grenades. As the French were preparing to board HMS Victory, HMS Temeraire, the second ship in the British windward column, approached from the starboard bow of FS Redoutable and fired on the exposed French crew with a carronade, causing many casualties.

At 13:55, the French Captain Lucas of FS Redoutable, with 99 fit men out of 643 and severely wounded himself, surrendered. The FS Bucentaure was isolated by HMS Victory and HMS Temeraire, and then engaged by HMS Neptune, HMS Leviathan, and HMS Conqueror; similarly, SPS Santísima Trinidad was isolated and overwhelmed, surrendering after three hours.

As more and more British ships entered the battle, the ships of the allied centre and rear were gradually overwhelmed. The allied van, after long remaining quiescent, made a futile demonstration and then sailed away. During the combat, Dionisio Alcalá-Galiano and Cosme Damián Churruca —commanders of the SPS Bahama and SPS San Juan Nepomuceno, respectively— were killed after ordering their ships not to surrender. The British took 20 vessels of the Franco-Spanish fleet and lost none. Among the captured French ships were Aigle, Algésiras, Berwick, Bucentaure, Fougueux, Intrépide, Redoutable, and Swiftsure. The Spanish ships taken were Argonauta, Bahama, Monarca, Neptuno, San Agustín, San Ildefonso, San Juan Nepomuceno, Santísima Trinidad, and Santa Ana. Of these, FS Redoutable sank, and SPS Santísima Trinidad and SPS Argonauta were scuttled by the British. FS Achille exploded, FS Intrépide and FS San Augustín burned, and FS Aigle, FS Berwick, FS Fougueux, and SPS Monarca were wrecked in a gale following the battle. (How is this not a movie yet?)

As Nelson lay dying, he ordered the fleet to anchor, as a storm was predicted. However, when the storm blew up, many of the severely damaged ships sank or ran aground on the shoals. A few of them were recaptured, some by the French and Spanish prisoners overcoming the small prize crews, others by ships sallying from Cádiz. Surgeon William Beatty heard Nelson murmur, "Thank God I have done my duty"; when he returned, Nelson's voice had faded, and his pulse was very weak. He looked up as Beatty took his pulse, then closed his eyes. Nelson's chaplain, Alexander Scott, who remained by Nelson as he died, recorded his last words as "God and my country." It has been suggested by Nelson historian Craig Cabell that Nelson was actually reciting his own prayer as he fell into his death coma, as the words 'God' and 'my country' are closely linked therein. Nelson died at half-past four, three hours after being hit.

Towards the end of the battle, and with the combined fleet being overwhelmed, the still relatively un-engaged portion of the van under Rear-Admiral Dumanoir Le Pelley tried to come to the assistance of the collapsing centre. After failing to fight his way through, he decided to break off the engagement, and led four French ships, his flagship the 80-gun FS Formidable, the 74-gun ships FS Scipion, FS Duguay-Trouin and FS Mont Blanc away from the fighting. He headed at first for the Straits of Gibraltar, intending to carry out Villeneuve's original orders and make for Toulon. On 22 October he changed his mind, remembering a powerful British squadron under Rear-Admiral Thomas Louis was patrolling the straits, and headed north, hoping to reach one of the French Atlantic ports. With a storm gathering in strength off the Spanish coast, he sailed westwards to clear Cape St. Vincent, prior to heading north-west, swinging eastwards across the Bay of Biscay (awful patch of sea to sail through), and aiming to reach the French port at Rochefort. These four ships remained at large until their encounter with and attempt to chase a British frigate brought them in range of a British squadron under Sir Richard Strachan, which captured them all on 4 November 1805 at the Battle of Cape Ortegal.

HMS Victory had been badly damaged in the battle and was not able to move under her own sail, so HMS Neptune towed her to Gibraltar for repairs. HMS Victory then carried Nelson's body to England, where, after lying in state at Greenwich, he was buried in St. Paul's Cathedral on 9 January 1806.

The Admiralty Board considered HMS Victory too old, and in too great a disrepair, to be restored as a first-rate ship of the line. In November 1807, she was relegated to second-rate, with the removal of two 32-pounder cannon and replacement of her middle deck 24-pounders with 18-pounders obtained from other laid-up ships. She was recommissioned as a troopship between December 1810 and April 1811. In 1812, she was relocated to the mouth of Portsmouth Harbour off Gosport (known as Gospit to us in the Navy), for service as a floating depot and, from 1813 to 1817, as a prison ship.

Major repairs were undertaken in 1814, including the fitting of 3 ft 10 in (1.2 m) metal braces along the inside of her hull, to strengthen the timbers. This was the first use of iron in the vessel structure, other than small bolts and nails. Active service was resumed from February 1817 when she was relisted as a first-rate carrying 104 guns. However, her condition remained poor, and in January 1822, she was towed into dry dock at Portsmouth for repairs to her hull. Refloated in January 1824, she was designated as the Port admiral's flagship for Portsmouth Harbour, remaining in this role until April 1830.

We are now nearing the end of Victory’s life at sea. Numerous times the Admiralty tried to destroy her but public outcry always stopped that and during one time even the King stepped in to stop it. She sprung numerous leaks including one which nearly sunk her at her mooring. She was turned into a school and opened to the public.

By 1921 the ship was in a very poor state, and a public Save the Victory campaign was started, with shipping magnate Sir James Caird as a major contributor. On 12 January 1922, her condition was so poor that she would no longer stay afloat, and had to be moved into No. 2 dock at Portsmouth, the oldest dry dock in the world still in use. A naval survey revealed that between a third and a half of her internal fittings required replacement. Her steering equipment had also been removed or destroyed, along with most of her furnishings

.

The Victory was the inspiration for the fictional Royal Navy ship HMS Dauntless in the 2003 Disney film Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl.

Listed as part of the National Historic Fleet, HMS Victory has been the flagship of the First Sea Lord since October 2012. Prior to this, she was the flagship of the Second Sea Lord. She is the oldest commissioned warship in the world and attracts around 350,000 visitors per year in her role as a museum ship. The current and 101st commanding officer is Lieutenant Commander Brian Smith, who assumed command in May 2015.

HMS Victory has also undergone emergency repair works to prevent the hull decaying and sagging. In 2017, it was discovered that the hull had been moving at a rate of half a centimetre each year, for a total of around 20 cm since the 1970s. To combat this, a new prop system was installed over a period of three years from 2018 to 2021, which allows for precise readings of the stresses on the hull and a more even distribution of the stress, which will help preserve the ship.

So there we go. If you’ve made it to the end then thank you. This will be my last post until after Christmas and the New Year. If I do have any more musings then I’ll make sure to start a draft. I want to review Critical Role as I love that show. If you love DnD then check them out.

Below I’ve added some links and a trailer for Master and Commander. Watch it, its awesome. Please like and share my post. Please comment and ask questions even if it’s about the modern Navy and I’ll try to answer. I love history and wish that I had studied it more seriously when I was at school in the 90’s. I hope everyone who reads has a very Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year.

Stay happy and healthy.

Vulkan

One of the best example of ships and sailors at sea of that period. Note that there’s no women serving (incredibly unlucky apparently) and CHILDREN as Naval Officers giving out orders. This is why you could be an Admiral at 30 back in those days whilst today you’d be lucky to be an Admiral at 55. Give it a watch.

Links to the battles that HMS Victory took part in.

1) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Ushant_(1778)

(2) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Battle_of_Ushant

(3) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Cape_St._Vincent_(1797)

(4) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Trafalgar

They certainly don't build them like they used to, do they! In regards to Flawless America's Just War Against British Oppression, sometimes I do think certain things would have been better if we'd stayed together (American Civil War wouldn't have happened maybe) but in the end both our countries got cucked by psychopaths anyway. 😆

Perhaps I can add, in shameless promotion of an article of mine, that this might amuse.

https://alphaandomegacloud.wordpress.com/2021/10/24/battle-of-trafalgar/