Good afternoon my good fellows. It’s Monday 26th February and I hope you all had a grand weekend. Last week I was at the medical centre for my knee and for once I looked up at the board in the entrance way. A big display to HMS Hood is there and I immediately knew I had to write about it in the same vein as that of my previous article featuring HMS Victory.

HMS Victory

So as a member of His Majesty’s Royal Navy, one of the most famous ships that is still commissioned (but not the oldest still sailing) is HMS Victory. There is actually a draft there which I’ve never managed to get which involves duties like conducting Colours and Sunset as well as opening up for the public in the mornings. You also sleep on board when …

So I will once again recount the story of one of the Royal Navy’s more famous ships. Please bear with me. I hope you enjoy it.

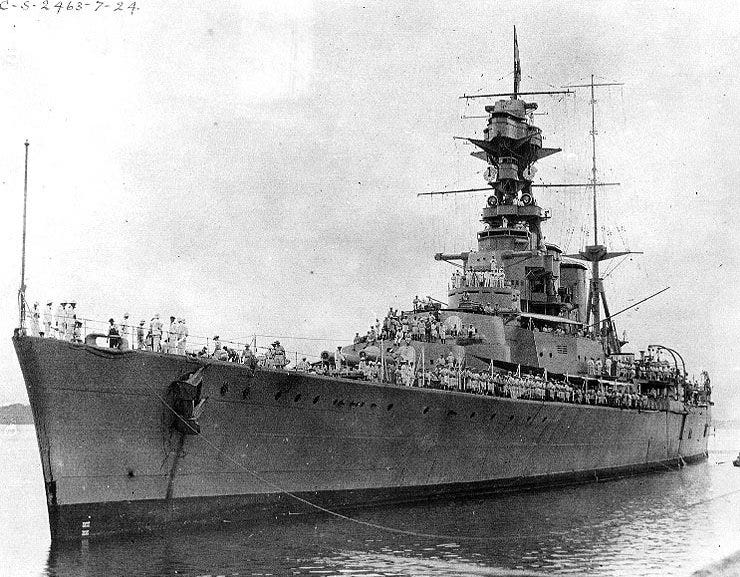

HMS Hood (pennant number 51) was a battlecruiser of the Royal Navy. HMS Hood was the first of the planned four Admiral-class battlecruisers to be built during the First World War. Already under construction when the Battle of Jutland occurred in mid-1916, that battle revealed serious flaws in her design, and despite drastic revisions she was completed four years later. For this reason, she was the only ship of her class to be completed, as the Admiralty decided it would be better to start with a clean design on succeeding battlecruisers, leading to the never-built G-3 class. Despite the appearance of newer and more modern ships, HMS Hood remained the largest warship in the world for 20 years after her commissioning, and her prestige was reflected in her nickname, "The Mighty Hood".

The Admiral-class battlecruisers were designed in response to the German Mackensen-class battlecruisers, which were reported to be more heavily armed and armoured than the latest British battlecruisers of the Renown and the Courageous classes. The design was revised after the Battle of Jutland to incorporate heavier armour and all four ships were laid down. Only HMS Hood was completed, because the ships were very expensive and required labour and material that could be put to better use building merchant ships needed to replace those lost to the German U-boat campaign.

The additional armour added during construction increased her draught by about 4 feet (1.2 m) at deep load, which reduced her freeboard and made her very wet. At full speed, or in heavy seas, water would flow over the ship's quarterdeck and often entered the mess decks and living quarters through ventilation shafts. This characteristic earned her the nickname of "the largest submarine in the Navy". The persistent dampness, coupled with the ship's poor ventilation, was blamed for the high incidence of tuberculosis aboard.

The main battery of the Admiral-class ships consisted of eight BL 15-inch (381 mm) Mk I guns in hydraulically powered twin gun turrets. The turrets were designated 'A', 'B', 'X', and 'Y' from bow to stern and 120 shells were carried for each gun. The ship's secondary armament consisted of twelve BL 5.5-inch (140 mm) Mk I guns, each with 200 rounds. They were shipped on shielded single-pivot mounts fitted along the upper deck and the forward shelter deck. This high position allowed them to be worked during heavy weather, as they were less affected by waves and spray compared with the casemate mounts of earlier British capital ships. Two of these guns on the shelter deck were temporarily replaced by QF 4-inch (102 mm) Mk V anti-aircraft (AA) guns between 1938 and 1939. All the 5.5-inch guns were removed during another refit in 1940.

The ship's main battery was controlled by two fire-control directors. One was mounted above the conning tower, protected by an armoured hood, and was fitted with a 30-foot (9.1 m) rangefinder. The other was fitted in the spotting top above the tripod foremast and equipped with a 15-foot (4.6 m) rangefinder. Each turret was also fitted with a 30-foot (9.1 m) rangefinder. The secondary armament was primarily controlled by directors mounted on each side of the bridge. They were supplemented by two additional control positions in the fore-top, which were provided with 9-foot (2.7 m) rangefinders, fitted in 1924–1925.

The armour scheme of the Admirals was originally based on that of the battlecruiser HMS Tiger with an 8-inch (203 mm) waterline belt. Unlike HMS Tiger, the armour was angled outwards 12° from the waterline to increase its relative thickness in relation to flat-trajectory shells. This change increased the ship's vulnerability to plunging (high-trajectory) shells, as it exposed more of the vulnerable deck armour. Some 5,000 long tons (5,100 t) of armour were added to the design in late 1916, based on British experiences at the Battle of Jutland, at the cost of deeper draught and slightly decreased speed. To save construction time, this was accomplished by thickening the existing armour, rather than redesigning the entire ship. HMS Hood’s protection accounted for 33% of her displacement, a high proportion by British standards, but less than was usual in contemporary German designs (for example, 36% for the battlecruiser SMS Hindenburg).

Construction of Hood began at the John Brown shipyard in Clydebank, Scotland, as yard number 460 on 1 September 1916. She was launched on 22 August 1918 by the widow of Rear Admiral Sir Horace Hood, a great-great-grandson of Admiral Samuel Hood, after whom the ship was named. Sir Horace Hood had been killed while commanding the 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron and flying his flag on HMS Invincible—one of the three battlecruisers which blew up at the Battle of Jutland. To make room in the shipyard for merchant construction, HMS Hood sailed for Rosyth to complete her fitting-out on 9 January 1920. After her sea trials, she was commissioned on 15 May 1920, under Captain Wilfred Tompkinson. She had cost £6,025,000 to build.

With her conspicuous twin funnels and lean profile, HMS Hood was widely regarded as one of the finest-looking warships ever built. She was also the largest warship afloat when she was commissioned, and retained that distinction for the next 20 years. Her size and powerful armament earned her the nickname of "Mighty Hood" and she came to symbolise the might of the British Empire itself.

Shortly after commissioning on 15 May 1920, HMS Hood became the flagship of the Battlecruiser Squadron of the Atlantic Fleet, under the command of Rear Admiral Sir Roger Keyes. After a cruise to Scandinavian waters that year, Captain Geoffrey Mackworth assumed command. HMS Hood visited the Mediterranean in 1921 and 1922 to show the flag and to train with the Mediterranean fleet, before sailing on a cruise to Brazil and the West Indies in company with the battlecruiser squadron.

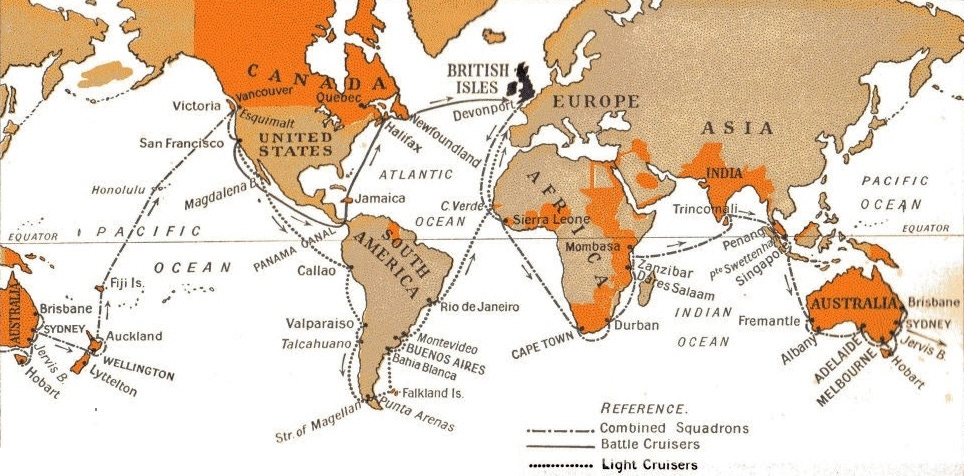

Captain John Im Thurn was in command when HMS Hood, accompanied by the battlecruiser HMS Repulse and the Danae-class cruisers of the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron, set out on a world cruise from west to east via the Panama Canal in November 1923. The objective of the cruise was to remind the dominions of their dependence on British sea power and encourage them to support it with money, ships, and facilities. They returned home 10 months later in September 1924, having visited South Africa, India, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and some smaller colonies and dependencies, and the United States.

HMS Hood was given a major refit from 1 May 1929 to 10 March 1931, and afterwards resumed her role as flagship of the battlecruiser squadron under the command of Captain Julian Patterson.

Captain Irvine Glennie assumed command in May 1939 and HMS Hood was assigned to the Home Fleet's Battlecruiser Squadron while still refitting. When war broke out later that year, she was employed principally to patrol in the vicinity of Iceland and the Faroe Islands to protect convoys and intercept German merchant raiders and blockade runners attempting to break out into the Atlantic.

HMS Hood was due to be modernised in 1941 to bring her up to a standard similar to that of other modernised First World War-era capital ships. She would have received new, lighter turbines and boilers, a secondary armament of eight twin 5.25-inch (133 mm) gun turrets, and six octuple 2-pounder "pom-poms". Her 5-inch upper-armour strake would have been removed and her deck armour reinforced. A catapult would have been fitted across the deck and the remaining torpedo tubes removed. In addition, the conning tower would have been removed and her bridge rebuilt. The ship's near-constant active service, resulting from her status as the Royal Navy's most battle-worthy fast capital ship, meant that her material condition gradually deteriorated, and by the mid-1930s, she was in need of a lengthy overhaul. The outbreak of the Second World War made removing her from service near impossible, and as a consequence, she never received the scheduled modernisation afforded to other capital ships such as HMS Renown and several of the Queen Elizabeth-class battleships.

HMS Hood and the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal were ordered to Gibraltar to join Force H on 18 June where HMS Hood became the flagship. Force H took part in the destruction of the French fleet at Mers-el-Kébir in July 1940. Just eight days after the French surrender, the British Admiralty issued an ultimatum that the French fleet at Oran intern its ships in a British or neutral port to ensure they would not fall into Axis hands. The terms were rejected, and the Royal Navy opened fire on the French ships berthed there. The results of Hood's fire are not known exactly, but she damaged the French battleship Dunkerque, which was hit by four fifteen-inch shells and was forced to beach herself.

HMS Hood was relieved as flagship of Force H by Renown on 10 August, after returning to Scapa Flow. On 13 September she was sent to Rosyth along with the battleships HMS Nelson and HMS Rodney and other ships, to be in a better position to intercept a German invasion fleet. When the threat of an invasion diminished, the ship resumed her previous roles in convoy escort and patrolling against German commerce raiders. HMS Hood, HMS Renown and HMS Repulse were deployed to the Bay of Biscay (an awful stretch of water if the weather is bad) on 5 November to prevent the heavy cruiser Admiral Scheer from using French ports after she had attacked Convoy HX 84, but the German ship continued into the South Atlantic.

In January 1941, the ship began a refit that lasted until March; even after the refit she was still in poor condition, but the threat from the German capital ships was such that she could not be taken into dock for a major overhaul until more of the King George V-class battleships came into service. Captain Ralph Kerr assumed command during the refit, and Hood was ordered to sea in an attempt to intercept the German battleships Gneisenau and Scharnhorst upon the refit's completion in mid-March. HMS Hood was ordered to the Norwegian Sea on 19 April when the Admiralty received a false report that the German battleship Bismarck had sailed from Germany. Afterwards, she patrolled the North Atlantic before putting into Scapa Flow on 6 May.

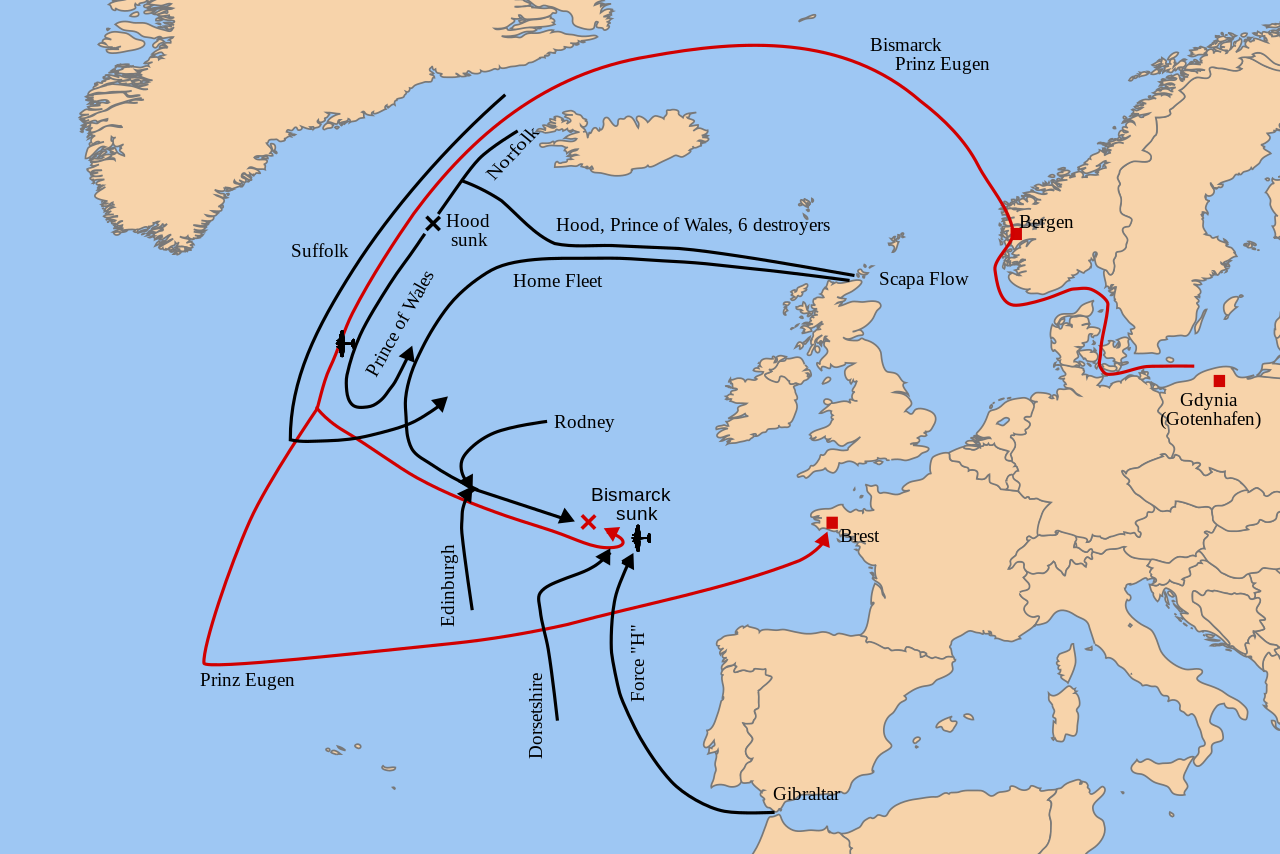

When Bismarck sailed for the Atlantic in May 1941, HMS Hood, flying the flag of Vice-Admiral Lancelot Holland, together with the newly commissioned battleship HMS Prince of Wales, was sent out in pursuit along with several other groups of British capital ships to intercept the German ships before they could break into the Atlantic and attack Allied convoys. The German ships were spotted by two British heavy cruisers (HMS Norfolk and HMS Suffolk) on 23 May, and Holland's ships intercepted Bismarck and her consort, the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, in the Denmark Strait between Greenland and Iceland on 24 May.

The British squadron spotted the Germans at 05:37 (ship's clocks were set four hours ahead of local time—the engagement commenced shortly after dawn), but the Germans were already aware of their presence, Prinz Eugen's hydrophones having previously detected the sounds of high-speed propellers to their southeast. The British opened fire at 05:52 with HMS Hood engaging Prinz Eugen, the lead ship in the German formation, and the Germans returned fire at 05:55, both ships concentrating on HMS Hood. Prinz Eugen was probably the first ship to score when a shell hit Hood's boat deck, between her funnels, and started a large fire among the ready-use ammunition for the anti-aircraft guns and rockets of the UP mounts.

Just before 06:00, while HMS Hood was turning 20° to port to unmask her rear turrets, she was hit again on the boat deck by one or more shells from Bismarck's fifth salvo, fired from a range of approximately 16,650 metres (18,210 yd). A shell from this salvo appears to have hit the spotting top, as the boat deck was showered with body parts and debris. A huge jet of flame burst out of Hood from the vicinity of the mainmast, followed by a devastating magazine explosion that destroyed the aft part of the ship. This explosion broke the back of HMS Hood, and the last sight of the ship, which sank in only three minutes, was her bow, nearly vertical in the water. A note on a survivor's sketch in the possession of the British Naval Historical Branch gives 63°20′N 31°50′W as the position of the sinking. HMS Hood sank stern first with 1,418 men aboard. Only three survived: Ordinary Signalman Ted Briggs (1923–2008), Able Seaman Robert Tilburn (1921–1995), and Midshipman William John Dundas (1923–1965). The three were rescued about two hours after the sinking by the destroyer HMS Electra, which spotted substantial debris but no bodies.

HMS Prince of Wales was forced to disengage by a combination of damage from German hits and mechanical failures in her guns and turrets after HMS Hood was sunk. Despite these problems, she had hit Bismarck three times. One of these hits contaminated a good portion of the ship's fuel supply and subsequently caused her to steer for safety in occupied France where she could be repaired. Bismarck was temporarily able to evade detection, but was later spotted and sunk on 27 May.

Memorials to those who died are spread widely around the UK, and some of the crew are commemorated in different locations. One casualty, George David Spinner, is remembered on the Portsmouth Naval memorial, the Hood Chapel at the Church of St John the Baptist, in Boldre, Hampshire, and also on the gravestone of his brother, who died while serving in the Royal Air Force in 1942, in the Hamilton Road Cemetery, Deal, Kent.

In 2001, British broadcaster Channel 4 commissioned shipwreck hunter David Mearns and his company, Blue Water Recoveries, to locate the wreck of HMS Hood, and if possible, produce underwater footage of both the battlecruiser and her attacker, Bismarck. This was to be used for a major event documentary to be aired on the 60th anniversary of the ships' battle. This was the first time anyone had attempted to locate HMS Hood's resting place. Mearns had spent the previous six years privately researching the fate of Hood with the goal of finding the battlecruiser, and had acquired the support of the Royal Navy, the HMS Hood Association and other veterans groups, and the last living survivor, Ted Briggs.

The search team and equipment had to be organised within four months, to take advantage of a narrow window of calm conditions in the North Atlantic. Organisation of the search was complicated by the presence on board of a documentary team and their film equipment, along with a television journalist who made live news reports via satellite during the search. The search team also planned to stream video from the remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV) directly to Channel 4's website.

After footage of Bismarck was collected, Mearns and the search team began scanning a 600-square-nautical-mile (2,100 km2) search box for HMS Hood; completely covering the area was estimated to take six days. Areas that Mearns felt were more likely to hold the wreck were prioritised, and the side-scan sonar located the battlecruiser in the 39th hour of the search.

Hood's wreck lies on the seabed in pieces among two debris fields at a depth of about 2,800 metres (9,200 feet). The eastern field includes the small piece of the stern that survived the magazine explosion, as well as the surviving section of the bow and some smaller remains, such as the propellers. The 4-inch fire-control director lies in the western debris field. The heavily armoured conning tower is located by itself, a distance from the main wreck. The amidships section, the biggest part of the wreck to survive the explosions, lies inverted south of the eastern debris field in a large impact crater. The starboard side of the amidships section is missing down to the inner wall of the fuel tanks and the plates of the hull are curling outward; this has been interpreted as indicating the path of the explosion through the starboard fuel tanks.

In 2002, the site was officially designated a war grave by the British government. As such, it remains a protected place under the Protection of Military Remains Act of 1986.

Some relics from the time of HMS Hood's sinking still exist. A large fragment of the wooden transom from one of HMS Hood's boats was washed up in Norway after her loss and is preserved in the National Maritime Museum in London. A metal container holding administrative papers was discovered washed ashore on the Norwegian island of Senja in April 1942, almost a year after the Battle of the Denmark Strait. The container and its contents were subsequently lost, but its lid survived and was eventually presented to the Royal Navy shore establishment HMS Centurion in 1981.

Other surviving relics are items that were removed from the ship prior to her sinking:

Two of HMS Hood's 5.5-inch guns were removed during a refit in 1935, and shipped to Ascension Island, where they were installed as a shore battery in 1941, sited on a hill above the port and main settlement, Georgetown, where they remain. The guns were restored by the RAF in 1984.

The Ascension Island guns saw action only once, on 9 December 1941, when they fired on the German submarine U-124, as it approached Georgetown on the surface to shell the cable station or sink any ships at anchor. No hits were scored, but the submarine crash-dived and retreated.

As a result of a collision off the coast of Spain on 23 January 1935, one of HMS Hood's propellers struck the bow of HMS Renown. While dry-docked for repairs, HMS Renown had fragments of this propeller removed from her bilge section. The pieces of the propeller were kept by dockyard workers: "Hood" v "Renown" Jan. 23rd. 1935 was stamped on one surviving example, and "Hood V Renown off Arosa 23–1–35" on another. Of the known surviving pieces, one is privately held and another was given by the Hood family to the Hood Association in 2006. A third piece was found in Glasgow, where HMS Hood was built. It is held by a private collector and stamped HMS HOOD v HMS RENOWN 23 1 35.

So there you have it. I hope you enjoyed the read. Perhaps I’ll do another one in the future if it takes my fancy. The Battle of Jutland springs to mind.

I hope I find you all happy and healthy.

Vulkan

Brave and noble fate.

Looking forward to reading this later Vulkan. I have to go out right now. But I had to say that my grandad served on the Hood in WW2. At least for a while. Not at the time of its sinking. He also served on the Ajax.